An important part of A Different Kind of Luxury is about the pleasures of making things by hand, about the both the pleasures and the deeper meaning of working with your own mind, heart, fingers and creativity to make something beautiful and tangible in this too-virtual world. As I wrote in the introduction to Chapter Two:

It wasn’t until I met the craftsman Osamu Nakamura that I could experience exactly how his “simple” life and his palpable contact with the physical world is actually so much richer than the hamster-wheel lives of overwork, busyness, and rush that so many of us have become accustomed to. By using his hands to provide for his needs, he has found a richness of heart and a sensitivity of perception that so many of us long for.

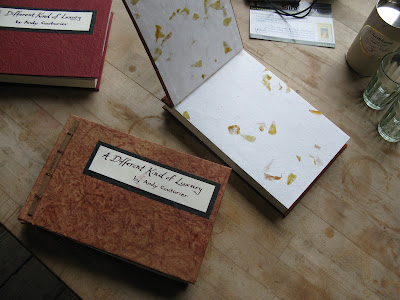

One of the things that Nakamura excels at making is hand bound books. Here are is one them.

Akira Ito (chapter Six) also bound dozens of his books by hand including a book on handmade paper making in Nepal. I wasn’t able to include that many photos of these in the final printed version, but I’d like to share some of them with you here:

Although I love sharing these with you so you can look at on them your screen, it doesn’t compare at all with holding such beautiful volumes in your hands. Paper is different than light pixels on plastic! Here’s a short excerpt about Nakamura and what he says about hand work:

“Making things with one’s own hands cultivates a certain generosity and openness of the heart. It nourishes that state of mind in the craftsperson themselves, which is intimately connected with an entire way of life.”

|

| One of a Kind Childrens Book by Akira Ito "The morning Wisteria Tree" |

As I spend more time with Nakamura, it occurs to me that it is as though the mastery he has achieved as a craftsperson suffuses all the other spheres of his life. He then shows me number of other books that he has bound by hand, and explains the Japanese method of sewing together the cloth-and-paper covers. I look at each of them and shake my head imagining how much time and care went into making them. Given how much labor they take, I realize that it is only possible to make a few copies of each, and that only a few people will ever see them. It seems a lot of effort for very little reward. But then I think that in contrast to a book published by machines in a factory, the simple potency and beauty of a hand-sewn book gives the reader pleasure of an entirely different order.

One of the books Nakamura has bound comprises a few photocopied pages on how to weave sandals from rice straw. Paging through it, I see how much my way of thinking about “craft” has changed over the period I have known him. Instead of craft being a “nice” pursuit with which to fill some unoccupied hours around the house, I have come to understand it as one of the most fundamental and ancient ways that humans have to meet their needs: baskets for winnowing grain, woven cloth to cover the body, forged and hammered iron tools with which to cultivate the soil, and woodblocks to print books and communicate with others. Craft is something every person needed before machines made everything we use. Spending time with Nakamura, I see that the process of making something like straw sandals or a handmade book cultivates humility while connecting us with something fundamental about our humanity: the interaction between the remarkable capacity of our own human hands and the ingenuity of our minds.

Here’s another short bit from the book, in Chapter Six, on consummate craftsman Akira Ito, who also writes beautiful essays on the life of the craftsperson:

And as I read his writing about craft, about being an artisan, I see that when he describes a technique it is more than just instructions or a purely technical discussion for practitioners. For him, the “how” of a craft cannot be divorced from the heart of the craftsperson. It is the core of their life, and the handwork is not simply a means to do something; it is the meaning itself.

In fact, it was the example of these two men who led me to hand bound some copies of A Different Kind of Luxury myself. I have completed several versions of my own, and I also brought some unbound copies with me to India last year, and I with some bookbinders there produced a limited edition series of five books. (I’m actually offering these personally for those who might like a copy of their own, please contact me at andy@theopening.org if you would like to buy one, there are three more left.)

Indeed, something made by hand has a tangible feel that cannot be described.